Philip the Fair, King of France

A while ago I read in a French interview with George R.R. Martin, the writer of Game of Thrones, that one of his inspirations for his saga was Les rois maudits [The Accursed Kings], the seven-volume historical fiction series written by Maurice Druon between 1955 and 1977. Apparently Druon wasn’t terribly proud of them, having dashed them off to make money. He went back later and rewrote the first few, which are amazingly well researched.

I love sagas, and as a fond reader of ancient Chinese history, which resembles them somewhat in its vast sweep, fascinating stories, lovable heroes, and sudden brutality, I had enjoyed the Game of Thrones books (in spite of two or three “he looked at her with loathing” in the first book….). So I plunged into the first volume, Le roi de fer [The Iron King] on a plane to the U.S. at Christmas, and just finished the last book yesterday. I feel bereft! That’s what a good saga does to you.

Les rois maudits opens with a bang. The strong, effective king Philip the Fair, grandson of Saint Louis, has united France, dominated the Papacy, which was then installed in Avignon, and rules with an iron fist. Coveting the riches of the powerful Knights Templar, he forces the Pope to declare them heretics, seizes their fortresses, and burns the last Grand Master, Jacques de Molay at the stake. The king is watching from his stand.

Suddenly, the voice of the Grand Master rose through the curtain of fire, and, as if speaking to every single person, hit everyone in the face. With a stupefying force, as he had done before Notre-Dame, Jacques de Molay cried,

“Shame! Shame! You see innocents dying. Shame on all of you! God will judge you.”

The terrified crowd had become silent. It was as if a mad prophet were being burned.

From this face on fire, the frightening voice declared:

“Pope Clement! Chevalier Guillaume! King Philip! Before the year is out, I call you to appear before the tribunal of God to receive your just punishment! Accursed! Accursed! All accursed till the thirteenth generation of your race!”

And before the year is out, the pope, the chief prosecutor Guillaume de Nogaret, and the king do indeed die.

“On this spot, Jacques de Molay, last Grand Master of the Order of the Temple, was burned on the 18th of March 1314”

In real life, as in the book, the Grand Templar met his end with great courage, and the common people collected his ashes with reverence. Today, in Paris, you can see the plaque marking this spot on the side of the Pont Neuf.

to be continued

Angel mothers of fiction

Cedric says goodbye to his mother, who nobly gives him up so that he can have the advantage of being brought up as a Lord by his grandfather, the Earl.

As a child, I didn’t get along well with my mother, who was overwhelmed with caring for lots of children, including one with special needs, mostly alone. I used to take refuge with book mothers, who always seemed angelic. Little Lord Fauntleroy (who by the way is an American! Did you know that?) calls his mother Dearest, which is enough to make most modern children gag; however, it appealed to Victorian mothers so much that quite a few actually dressed their boys like this:

A child in the 1888 theatrical version of Little Lord Fauntleroy

Most of those Victorian angel mothers, I now know, had servants. They never had to wash dishes, go to the grocery store, change diapers or stand over a hot stove. Much easier for your child to adore you when it sees you in the drawing room for an hour or two a day!

The story behind the story: Kipling’s Kim, part II

Since I am writing a book about a boy spy in Asia (although in ancient China, not British colonial India), I was rereading Kim. The book is full of the life of India in the 1800s, in all its diversity and vigor. I love learning how Kipling was inspired by real people, places and events in his story.

One of the most intriguing characters in the book is the mysterious Lurgan Sahib, who runs a jewelry store in Simla, in the Himalaya. Today, Simla is a sleepy little town, but when the British ran India, the colonial administration would move there for the hot months, and for more than half the year, Simla was effectively the capital of India.

Lurgan Sahib teaches Kim how to observe. He was based on the real, fascinating “Alexander Jacob,” whom Kipling seems to have met. Peter Hopkirk, in Quest for Kim, writes: “Claiming to be a Turk, he was believed by some to be of Armenian or Polish Jewish parentage, though born in Turkey. ‘He was of the humblest origin,’ the obituarist continues, ‘and when ten years old was sold as a slave to a rich pasha, who, discovering the boy’s uncommon abilities, made a student of him.'” He became free on the death of his master, made a pilgrimage to Mecca in disguise, worked his way from the Arabian peninsula to Bombay, and ended up as a gem-dealer in Simla. Many people who knew him apparently believed he had supernatural powers, and this is hinted at in Kim. Peter Hopkirk, too, writes that odd things happened to him while he was trying to find out more about Jacobs. Among other misfortunes, he lost all of his notes for his book. “Although I cannot say I seriously believe in messages or warnings from beyond the grave, this was not the only thing that happened while I was searching for Jacob’s will…Perhaps it was now time to lay off Jacob before something far worse befell me!”

At about age sixteen, Kim is reunited with the old Tibetan lama who has paid for his expensive boarding school.

Kim and the lama. These illustrations were by Kipling’s father, who knew the real man who was the model for Teshoo Lama. The swastika symbolizes the endless cycle of birth and death that Buddhists and Hindus hope to escape. Unlike the Nazi swastika, which is set on the diagonal, the Hindu one sits squarely on its base.

Kim and his lama make their way to the Himalayan foothills; the lama “drew a deep double-lungful of the diamond air, and walked as only a hillman can. Kim, plains-bred… sweated and panted astonished. ‘This is my country,’ said the lama.” One day in the hills, they meet Hurree Babu, one of Creighton Sahib’s top spies, who is pretending to be a “courteous Dacca physician” but is actually in the hills looking for two men who have come from Russia.

During the 1800s, the Russians continually advanced their frontiers, and the British in India definitely felt the threat. This is “the Great Game” in Kim. In reality, the Russians came thousands of miles closer to India during that century; but in the book, they are warded off by the network of spies set up by Creighton Sahib. Hurree Babu and Kim and the unwitting lama cause the Russian and French officer to lose all their maps and other possessions and feel lucky they are still alive. The lama and Kim take refuge with “the woman of Shamlegh,” Lispeth, the polyandrous mistress of a remote community on the edge of a 2000-foot cliff. Kipling wrote an entire story about her; it’s sad.

At the end of the story, the lama and Kim, having thwarted the Russians’ plot, return to the Indian lowlands and the lama happens across a farm stream he is sure was the Buddha’s.

“Certain is our deliverance! Come!” He crossed his hands on his lap and smiled, as a man may who has won Salvation for himself and his beloved.

The story behind the story: Kipling’s Kim

Kim is one of my favorite books (and the name of my first boyfriend– he was named after it. For a long time that put me off reading the book). I’m aware that for a lot of people, independent of the story, the book is problematic because of its unapologetic colonialism. But it’s a really good read and, approached with an open mind, a fascinating glimpse of India under British rule in the late 1800s, with all the wild variety and color of its landscape and its many different ethnic groups, religions and languages.

Recently I read a book by Peter Hopkirk (who also wrote The Great Game) on the sources and original people and places that inspired Kipling to write Kim.

Hopkirk, who died last year, didn’t have the advantage of the internet in writing Quest for Kim, which was published in 1996. But I do! Using Hopkirk’s book’s identifications, I went looking for pictures to illustrate the story behind the story of Kim, the boy spy.

The book begins in Lahore, which was once a great Indian city and is now in Pakistan and almost completely Muslim. A bunch of street urchins, including Kim, are playing on the great cannon, Zam-Zammah. It’s still there.

Into the chaotic city walks a creature from another world– a lama, abbot of a Tibetan monastery, come down from the Himalaya to look for the Buddha’s stream of enlightenment. He’s been told to ask “the keeper of the wonder house” – the museum curator. Kipling’s father, Lockwood, in fact: a scholarly, gentle man.

Into the chaotic city walks a creature from another world– a lama, abbot of a Tibetan monastery, come down from the Himalaya to look for the Buddha’s stream of enlightenment. He’s been told to ask “the keeper of the wonder house” – the museum curator. Kipling’s father, Lockwood, in fact: a scholarly, gentle man.

I was delighted to learn from Hopkirk’s book that the lama, too– the second hero of Kim– was also based on a real person. Here is a distinguished red-hat lama of today, who looks like the lama in the story to me: “such a man as Kim, who thought he knew all castes, had never seen. He was nearly six feet high, dressed in fold upon fold… and not one fold of it could Kim refer to any known trade or profession. At his belt hung a long openwork iron pencase and a wooden rosary such as holy men wear. On his head was a gigantic sort of tam-o’-shanter… His eyes turned up at the corners.”

“I am no Khitai [Chinese],” says the old man, “but a Bhotiya (Tibetan), since you must know– a lama– or, say, a guru in your tongue.”

Hopkirk identified the lama’s monastery as Tso-chen, which you can see on the map in the bottom left quadrangle. It is very remote, but today, tourists can visit the Mendong monastery in Tso-chen (now Coqên).

Hopkirk identified the lama’s monastery as Tso-chen, which you can see on the map in the bottom left quadrangle. It is very remote, but today, tourists can visit the Mendong monastery in Tso-chen (now Coqên).

A third hero of the book is the Pathan horse merchant Mahbub Ali. Kim meets him at a caravansery, an inn with space for camels and wares. Here is a picture of one in Peshawar that probably looked much like the one Kim visits in Lahore.

And here is Kipling’s father’s illustration of Mahbub Ali himself: a Pashtun (Pathan) from Afghanistan. It’s exactly how I imagine him. “The big burly Afghan, his beard dyed scarlet with lime (for he was elderly and did not wish his gray hairs to show) knew the boy’s value as a gossip.” He is a Muslim and likes to say “God’s curse on all unbelievers!” before doing something kind for the unbeliever in question. He is also a master spy.

And here is Kipling’s father’s illustration of Mahbub Ali himself: a Pashtun (Pathan) from Afghanistan. It’s exactly how I imagine him. “The big burly Afghan, his beard dyed scarlet with lime (for he was elderly and did not wish his gray hairs to show) knew the boy’s value as a gossip.” He is a Muslim and likes to say “God’s curse on all unbelievers!” before doing something kind for the unbeliever in question. He is also a master spy.

Kim and the lama set out on the Grand Trunk Road that runs east-west across India. Today, much of it is a major highway.

“See, Holy One–” says an old man to the lama, “the Great Road which is the backbone of all Hind. For the most part it is shaded, as here, with four lines of trees; the middle road– all hard– takes the quick traffic…. Left and right is the rougher road for the heavy carts– grain and cotton and timber, bhoosa, lime, and hides. A man goes in safety here– for at every few kos is a police station….All castes and kinds of men move here. Look! Brahmins and chumars, bankers and tinkers, barbers and bunnyas, pilgrims and potters– all the world going and coming.”

“And truly,” continues the narrator, “the Grand Trunk Road is a wonderful spectacle. It runs straight, bearing without crowding India’s traffic for fifteen hundred miles– such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world.”

Kim sneaks up into the bushes to Colonel Creighton’s villa in Umballa, just off the Great Trunk Road, to pass a secret message to the colonel from Mahbub Ali. Peter Hopkirk was able to find the only villa it could have been in the modern town of Ambala, and this picture in Quest for Kim was drawn from his photo. The message, as Kim guesses, has nothing to do with horses and is about rebellious hill rajahs.

Thomas George Montgomerie of the Indian Survey was undoubtedly the original of Colonel Creighton, who manages Kim’s career as a spy.

Thomas George Montgomerie of the Indian Survey was undoubtedly the original of Colonel Creighton, who manages Kim’s career as a spy.

“An officer of great ingenuity,” writes Hopkirk, “he trained these hand-picked individuals in clandestine surveying techniques devised by himself which would permit them to work undercover beyond the frontiers of British India, thus enabling the Survey to produce maps of the strategic approaches which an invader might use.

“Montgomerie first taught his men, through exhaustive practice, to take a pace of known length which would remain constant whether walking uphill, downhill or on the level. Next he devised furtive ways whereby they could keep a precise but discreet count of the number of such measured paces taken during a long day’s march. Some travelled as Buddhist pilgrims, with rosaries and prayer-wheels, which Montgomerie’s workshops at Dehra Dun, the Survey’s headquarters, cunningly doctored for clandestine use…. ”

More in the next post.

Freedom for children

As a girl, I was a bookworm, but we lived in a beautiful part of upstate New York and from time to time I would venture outside to explore, going deep into woods, up mountain streams, across frozen ponds. Once I even fell into a drift of powder snow over my head and literally had to swim out. I don’t remember my parents ever particularly worrying about my siblings and me. Of course, there were seven of us.

My father grew up in Malden, a then all-Irish town just north of Boston. When he was about ten, he and his best friend were allowed to bicycle to Thoreau’s Walden Pond (red arrow, above), ten miles away as the crow flies, but 23 miles by road, and spend the night there camping out. They were city kids and had no idea how to camp. They built a fire under a can of beans and it exploded!

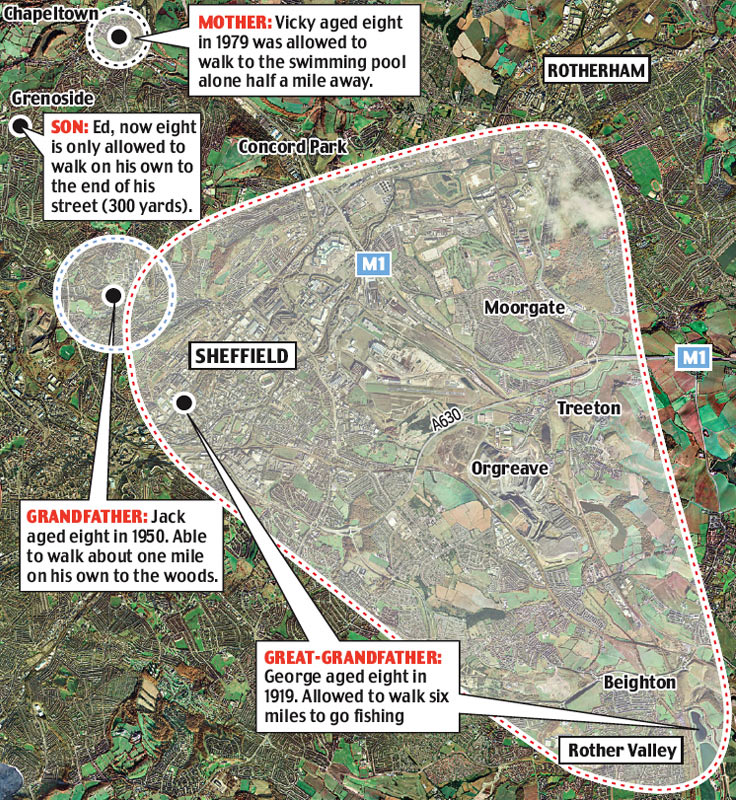

Children nowadays, though, don’t seem to get as much freedom to roam. A British study chronicled the extent of the crippling of children’s freedom and reported that four out of five children had basically no contact with nature.

In contrast, read this account of a river adventure. It’s a letter to Harper’s Young People, a children’s magazine, published on August 31, 1880.

Moline, Illinois

I live on the Mississippi River, which is over a mile wide here. I am thirteen years old, and a reader of Young People. I think “The Moral Pirates” is the best story of all.

Two of my companions, Frank and Rob, had read the story; so we made up our minds that instead of cruising we would camp out for a week. Frank’s father owned a large row-boat, which he said we might take, and I took my tent and dog. We laid in enough provisions to last a month.

So after a good deal of trouble we got started. We landed about three miles from here, on the other side of the river. It was a splendid place to camp. The ground was sandy, and was hemmed in by trees. The first night passed well enough. The next morning Frank and I rowed across the river for milk. As we were nearing camp on our way back, a large steamboat nearly ran us down. The swell nearly capsized us, and as it was, we got pretty wet.

We concluded that we could not stand that sort of thing, and made up our minds to start for home the next day, where we arrived to be well laughed at.

I’m sure life is safer for children now, but I think we’ve lost something, don’t you?

Reading an Edwardian novel: “Indian summer”

I love charity bookshops, and for years I’ve collected old children’s books with pretty covers. But unlike a lot of collectors, I actually read the books, too.

I love charity bookshops, and for years I’ve collected old children’s books with pretty covers. But unlike a lot of collectors, I actually read the books, too.

I’ve seen this book, The O’Shaughnessy Girls, so often in such bookstores that I knew it must once have been very popular. So finally I bought and read it. It was indeed a good read. It’s about four sisters growing up in Castle Dermot, Ireland (their mother an English earl’s daughter, their father an Irish nobleman, “connected of old with the O’Sullivan Bere”– my own relatives, so of course I like him). The story is charming and must have seemed a bit daring fo r the times– one of the girls runs away to be an actress, and one of the boys, a “gentleman’s son,” works

r the times– one of the girls runs away to be an actress, and one of the boys, a “gentleman’s son,” works

as a farm laborer, disguising himself as “Jim from Connaught,” to escape from a tragedy. A young lady whose father has lost all his money opens a tea shop, even though “ladies” don’t do such things. An irredeemably vulgar, but kind and lovable, woman of the neighborhood is raising her own children to be ladies and gentlemen by sending them to good schools with her new money.

It’s amusing to read, when Lady Sybil and her youngest daughter return from a long journey, that “the servants were gathered to welcome back those who had been sadly missed when absent. Mrs. Flynn, the housekeeper; Keefe, the butler; Peter Walsh, the gardener, all old retainers, were there, with a younger staff of Norahs, and Bridgets, and Dans, of indoors and out-of-doors. Lady Sybil’s household was a modest one….”

The most poignant thing, though, the thing that sent a shiver down my spine when I read it, was this passage. One of the sisters has just become engaged to a wonderful young man.

“There was Indian summer on the land, and the mother and daughters spent hours together in the garden, walking in the lanes of late hollyhocks and dahlias, or sitting on the green terrace looking down on the river… their future shining before them with the glory of the rising sun.”

It was 1911.