When I was 12, my family lived at the bottom of this mountain.

As a girl, I was a bookworm, but we lived in a beautiful part of upstate New York and from time to time I would venture outside to explore, going deep into woods, up mountain streams, across frozen ponds. Once I even fell into a drift of powder snow over my head and literally had to swim out. I don’t remember my parents ever particularly worrying about my siblings and me. Of course, there were seven of us.

My father grew up in Malden, a then all-Irish town just north of Boston. When he was about ten, he and his best friend were allowed to bicycle to Thoreau’s Walden Pond (red arrow, above), ten miles away as the crow flies, but 23 miles by road, and spend the night there camping out. They were city kids and had no idea how to camp. They built a fire under a can of beans and it exploded!

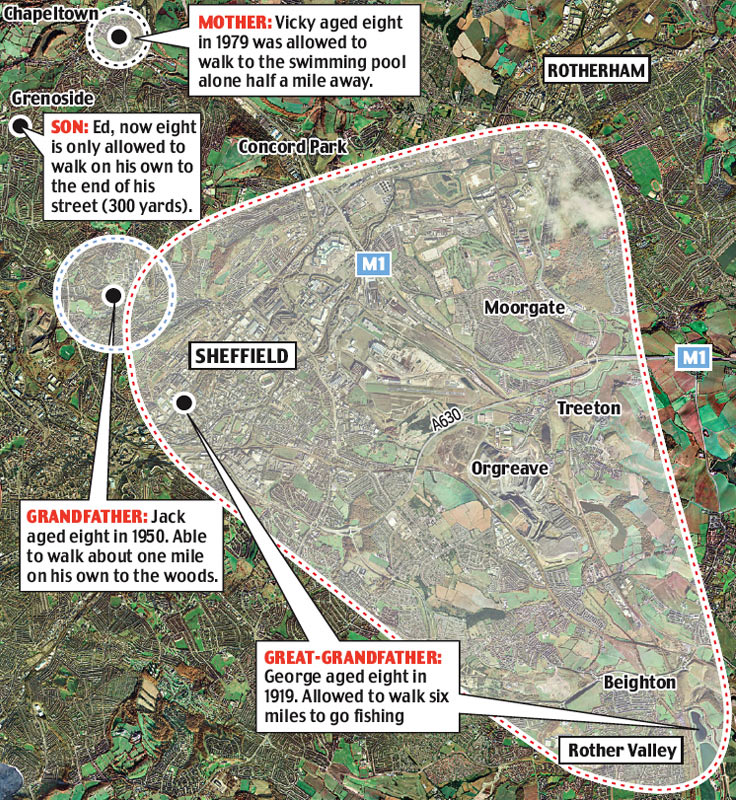

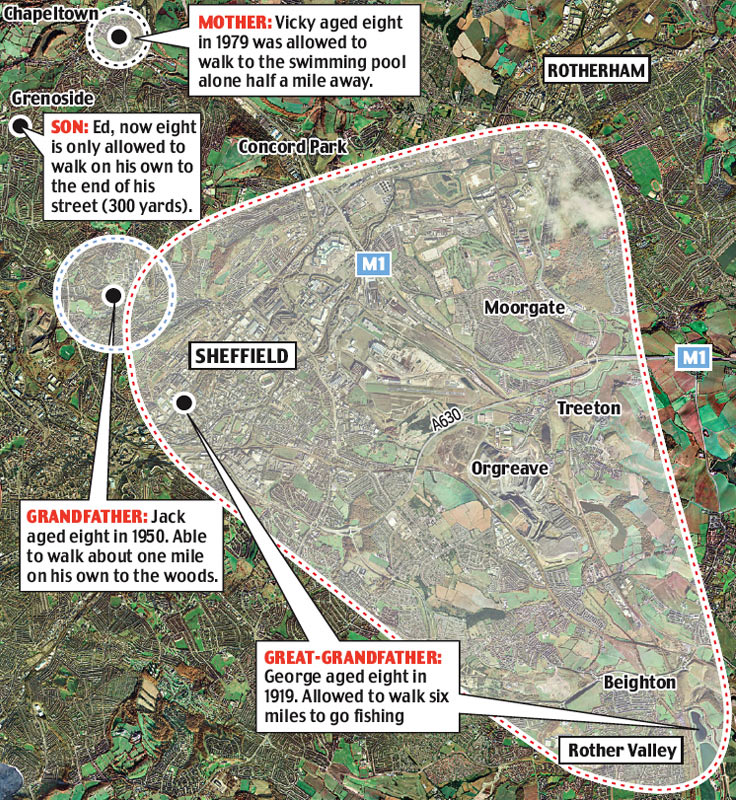

Children nowadays, though, don’t seem to get as much freedom to roam. A British study chronicled the extent of the crippling of children’s freedom and reported that four out of five children had basically no contact with nature.

In contrast, read this account of a river adventure. It’s a letter to Harper’s Young People, a children’s magazine, published on August 31, 1880.

The Mississippi River at Moline

Moline, Illinois

I live on the Mississippi River, which is over a mile wide here. I am thirteen years old, and a reader of Young People. I think “The Moral Pirates” is the best story of all.

Two of my companions, Frank and Rob, had read the story; so we made up our minds that instead of cruising we would camp out for a week. Frank’s father owned a large row-boat, which he said we might take, and I took my tent and dog. We laid in enough provisions to last a month.

So after a good deal of trouble we got started. We landed about three miles from here, on the other side of the river. It was a splendid place to camp. The ground was sandy, and was hemmed in by trees. The first night passed well enough. The next morning Frank and I rowed across the river for milk. As we were nearing camp on our way back, a large steamboat nearly ran us down. The swell nearly capsized us, and as it was, we got pretty wet.

We concluded that we could not stand that sort of thing, and made up our minds to start for home the next day, where we arrived to be well laughed at.

I’m sure life is safer for children now, but I think we’ve lost something, don’t you?